|

What Hypnosis Really

Does to Your Brain

Gizmodo, by Esther Inglis-Arkell, 3/08/12

Most people agree that hypnosis does something to your brain —

specifically something that makes people make fools of themselves at

hypnotist shows. But how does it actually affect the human brain? Can it

make people recall events perfectly? Are post-hypnotic suggestions a bunch

of baloney? What is the truth about hypnotism?

A History of Hypnosis

Nearly every culture in the world has a history of hypnotic trances. Some

only considered them spiritual or eerie, but most began to make use of

them as soon as they were discovered. India and China have ancient records

showing hypnotic trances being used to relieve pain during surgery. The

practice migrated to Europe, where in 1794 a young boy having an operation

for a tumor was put under. The boy was Jacob Grimm, who grew up to write

about quite a few hypnotic trances in his and his brother's book of fairy

tales.

As ether and anesthesia came in, hypnosis went out. The medical community

at large rejected its claims to pain reduction and hypnotic suggestions.

Meanwhile, Hollywood embraced it as a plot device, adding on fantastic

properties that made it seem still more outlandish to the public. It

finally settled in the entertainment industry, where it does have the

power to make people do extremely silly things, with extreme sincerity.

(Watching some dead-serious kids give Grammy speeches as if they were

Ricky Martin convinced me that hypnotism must have power over people.) But

the extent of its power has always been debated.

How Hypnosis Affects the Brain

A person in a hypnotic state will appear tuned-out, and one of the marks

of true hypnosis is a decrease in involuntary eye movement to the point

where deeply hypnotized people will have to be reminded to blink. This

gives an observer the impression that the hypnotized aren't paying

attention. In fact, they're playing hyper-attention. Compared to a resting

brain, many areas come online when a person is put into a hypnotic trance.

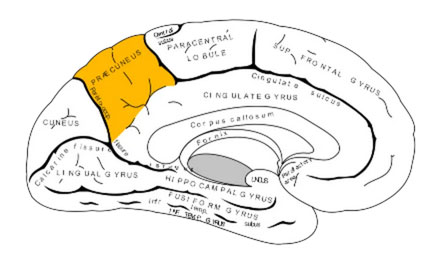

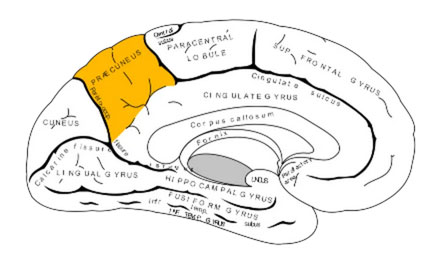

All the areas that flare to life during hypnosis are also engaged when a

person is concentrating on mental imagery — except one. Like many areas of

the brain, the precuneus lights up during many different tasks, all of

them having to do with a consciousness of self. It also deals with

visuospatial aspects of the brain, letting us know where we are in space.

In essence, when we're hypnotized, people are able to

concentrate intensely on self-created imagery (or imagery that suggested

to them) but do not place their selves as part of that imagery. They've

lost the reminder of what they personally do and what normal judgments

they make, while increasing their ability to think about a whole range of

imaginary situations. This explains the way adults can act out under the

influence of hypnosis, or how they might remain calm and collected in

situations that would otherwise terrify them. But how far does it go?

The Power of Hypnosis

One of the most incredible feats people under hypnosis are supposed to

perform is the ability to remember details of a past event that a person

has consciously forgotten. In movies everyone, under hypnosis, suddenly

has a photographic memory (right up until they try to see the killer's

face). There is debate, and some hypnotherapists claim that they have

helped people retrace their steps through hypnosis and remember locations

of, say, lost items or valuable papers.

But a larger study at Ohio State University cast doubt on whether hypnosis

can actually enhance your memory to such an extent. When two groups of

students, one hypnotized and one only relaxed, were asked about the dates

of certain historical events, the groups performed equally well. The only

difference was, when they were informed that there were some errors in

their answers, the hypnotized group changed fewer answers than the

unhypnotized group. Hypnosis got a more infamous reputation when it was

used by psychologists to 'recover' lost memories, often of childhood

abuse, that never happened.

But hypnosis does have the power to tap into memory in ways that other

techniques do not. Most importantly, it has the ability to induce

temporary, reversible amnesia. This condition is extremely rare, as many

amnesiacs don't recover their memories, and some unlucky ones can't make

new memories.

Although not all hypnotized patients can have their memories suppressed,

and no one suppresses their memories unless they're told to, the effects

can be startling. For one thing, the entire memory can be brought back

with a word. This indicates that hypnosis doesn't obliterate memories, it

just temporarily shuts off the retrieval system. One woman was told she

couldn't remember the word 'six,' and so answered 'seven' to mathematical

questions. A man forgot his own name. Any memory could be suppressed.

But the memory didn't go away. A group of students were hypnotized and

told to forget a short film they had just watched. While unable to answer

questions about the film, they had no problem remembering if the film was,

for example, shot on a handheld camera. It was only the content that was

suppressed. This ability to remember and react to the context of a thing

without remembering the thing itself is the post-hypnotic suggestion. It's

a suggested habit that makes sense in context (like reaching for a cell

phone when hearing a ringtone) but not at that moment (if you deliberately

left your cell phone at home). It just doesn't occur to the person to

think of what they're reacting to before they react.

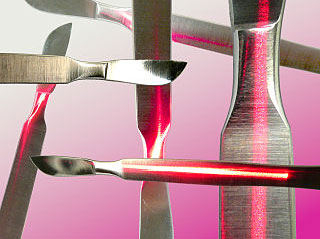

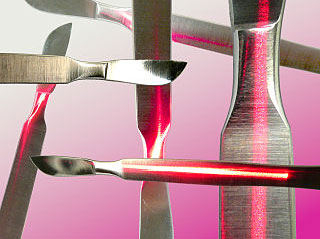

Another amazing hypnotic ability is, supposedly,

suppression of pain. While it makes sense that people might feel less

self-conscious, what with the part of their brain that feels

self-consciousness offline, and that their perception might be altered by

the part of the brain that governs perception, but pain is different. One

of the primary functions of pain is to force someone out of the reverie

they're in and make them pay attention to reality. Pain is the outside

world breaking in.

But scientists studying perception think our experience is shaped far more

by what we expect the stimulus to be than the stimulus itself. There are

ten times as many nerve fibers carrying information down as carrying it

up. Most people will have experienced feeling a shape in their pockets and

being disoriented until they remember that it's a wadded up receipt, at

which point the sensations seem familiar.

More to the point, most people will remember an itching or sting that,

when they see a more serious injury than they expected, will blossom into

pain. A hypnotized person undergoing surgery, for example, may be able to

convince themselves that they're experiencing the discomfort of a bug bite

instead of a scalpel. That, along with a state of enforced relaxation, can

make all the difference.

But the shadiest aspect of hypnotism — what it can make an entranced

person do — is still shrouded in mystery. Most hypnotists take pains to

stress that no one is enslaved when they're in a hypnotized state, and

that they can't be made to do something they don't want to do. Of course,

that is the line they'd take.

Scientists are, understandably, reluctant to give

people the suggestion to murder someone under hypnosis, and test the

results. Perhaps the best test of this isn't science, but history.

Although there have always been legends of people under the direction of

an evil puppet-master committing unspeakable acts against their will,

there have been no actual cases. So don't worry about going to those

hypnotist shows. Just . . . don't sit in the front.

Source:

https://io9.gizmodo.com/what-hypnosis-really-does-to-your-brain-5891504

NOTE: This is a very good piece on the power

of hypnosis, but for the second to last line of this article. HypnosisReality.com has established the history with close to 100

documented cases of hypnosis abuse. This website has made an effort to

reach out to the author of this article, to offer the historical evidence

that has been collected, in the hopes that it will complete her

relatively decent understanding of hypnosis.

Our bet is, she will get the big picture and

understand it all.

|

Links

More posts from Esther Inglis-Arkell

Gizmodo |